Good Presentations: Credibility and Story Telling

- John Schneider

- Oct 3, 2015

- 3 min read

Recently, I had the pleasure of attending one of Edward Tufte’s one-day courses—Presenting Data & Information. For almost three decades, Tufte has been a leader in the visualization of data and statistical information, a field he refers to as analytic design.

One point that stuck with me was his emphasis on making presentations “not suck.” According to Tufte, the two main ingredients in the recipe for a not-so-sucky presentation are:

Establishing Credibility

Telling an Interesting Story

So the question is, how to do these things?

Establishing Credibility

You as the speaker must recognize the audience’s curiosity about your motivations for presenting this information, your methods to arrive at your conclusions, and your evidence to back it all up. In a nutshell, you must give your audience a reason to believe.

Motivations

Be up front with your audience and make your motivations clear. For example, are you motivated because a large corporation funded your research and so now you feel obligated to scratch their backs? Or is your work more independent and objective?

Methods

Explain how you’ve arrived at your conclusion. Is it anecdotal, based on personal observations and conversations with others? Is it a summation of your lifelong experience and the patterns you’ve gleaned? Or is it more concrete and evidence-based? If so, how was your research conducted?

Evidence

Reveal the facts to your audience and be careful how you present them. Are you cherry-picking data to support your assumptions, or are you letting the data speak for itself?

Telling an Interesting Story

If you’re at all familiar with Edward Tufte, you know one of his commandments is “No PowerPoint.” According to Tufte, PowerPoint, with its ready-made designs, causes the presenter to rely on bulleted templates that “weaken verbal and spatial reasoning, and almost always corrupt statistical analysis.” PowerPoint presentations all too often become a “follow the bouncing ball” exercise, where the audience listens as the presenter reads off the main points, bullet by droning, boring bullet. What’s his solution? Supergraphics.

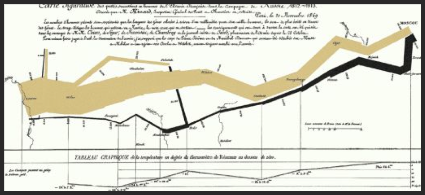

Graphical depiction of Napoleon’s army, marching from Moscow and back.

Initially, rather than walking your audience through your main points and prepping them for your final, astounding insights, Tufte recommends you resent a document (which he calls a supergraphic) that allows them to take it all in.

One of the most famous examples of a supergraphic that Tufte uses is Charles Joseph Minard’s graph of the dwindling number of Napoleon’s army as it marched to Moscow and back in 1812. With very little textual explanation, it contrasts the size of the army’s march towards Moscow (brown line) with its return (black line); the size of the army is equal to the width of the lines. The temperature is plotted on the lower graph to show how the cold affected the army’s size.

Supergraphics kick things off on an interesting visual note, which is usually more engaging and interesting than a spoken preamble. Also, people read and scan faster than you can talk. A supergraphic allows audience members to use their own cognitive style to warm up to your ideas. Let them take it all in on their own; later, highlight what you believe are the most important, salient points.

Considering a Strategic & Tactical Framework

Along with credibility and story telling, you need a good framework for your thoughts. Here are some items to keep in mind to weave together a logical and engaging presentation.

Strategic

State the problem or issue — What’s happening.

Show your audience the relevance — Why they should care.

Present a solution — What they should do.

Tactical

Provide a high-resolution data dump — Supergraphic.

Quickly summarize, highlighting important points — Present your ideas.

Allow time for a cross-examination with audience — Q&A

One final thought: You probably have more in common with your audience than you think. They’ve come to listen to your presentation because they most likely share a common interest, so don’t waste too much time on background. Jump right in and engage them from the start.

Comments